Last week, I wrote about my experiences with traditional publishing and the reasons why I became interested in self-publishing. But when I looked into self-publishing, what did I find?

In my writing, I have a few main goals. For one, I like to write about topics as I learn about them, because the act of writing helps to clarify my own understanding and viewpoint on the subject. I felt compelled to write about Rome and China because I was in the process of learning so much about both societies myself. I felt compelled to write The Myth of the Thucydides Trap because I studied the concept in great detail, and wanted to share what I learned. I decided to translate The Art of War after I read many texts from the period in the original Chinese and gained insights that had escaped me when I read them in English earlier in my life. I’m not choosing my topics based on marketability or any expectation of success- they come naturally out of what I find interesting or rewarding in my own life.

Two, I like to jump the fence between what’s accessible to the average reader and what’s been siloed off by specialists and academics. I think the modern academy has a bizarre tendency to produce useful ideas and knowledge then lock it up behind journal paywalls, technical jargon, and opaque references to a “canon” that only doctoral candidates have read. I’ve learned to jump many of these hurdles so you don’t have to. I aim to write books that any curious and reasonably intelligent person can pick up, understand, and benefit from, and that strip away the mystique (and layers upon layers of gatekeeping) that block most people from accessing specialist knowledge.

Lastly, I want to lead by example and encourage more people to write about whatever they are passionate about, even if the audience is small and the opportunities for profit are limited. I’m firmly against the idea that writing and publishing is only for some select, special group of people. I’m even more firmly against the idea that a skill or craft is only worth developing if you expect to make a lot of money using it. If we all wrote more, and read more of what others wrote, the world would be better for it. I found that no one was self-publishing the kind of books that I like to read and write, so I guess that means I have to be the first.

All three of these goals run contrary to the needs of traditional publishing. Traditional publishers want someone who can at least pretend to be a credentialed expert who already knows it all and has already done it all. They don’t want to take chances on amateurs or autodidacts. This necessarily means they’re deeply invested in the mystique of these certified experts- the professor with a doctorate, the executive with an MBA, the novelist with an MFA from a famous writer’s workshop. If we don’t actually think these people are all that special, if we think that their knowledge and skills are (or at least should be) accessible to everyone, then why should we limit the act of publishing books to them? Lastly, publishers need to make money, and since book sales are so monstrously hard to predict, they need to try for a few multimillion-copy bestsellers to offset all the rest that hardly break even, or don’t break even at all. If you can do it for them once, they want you to do it again. This idea of the smash hit author as a consummate money-making professional clashes with my own goal of writing as a passionate amateur, motivated by the joy of writing even if there is little or no economic payoff.

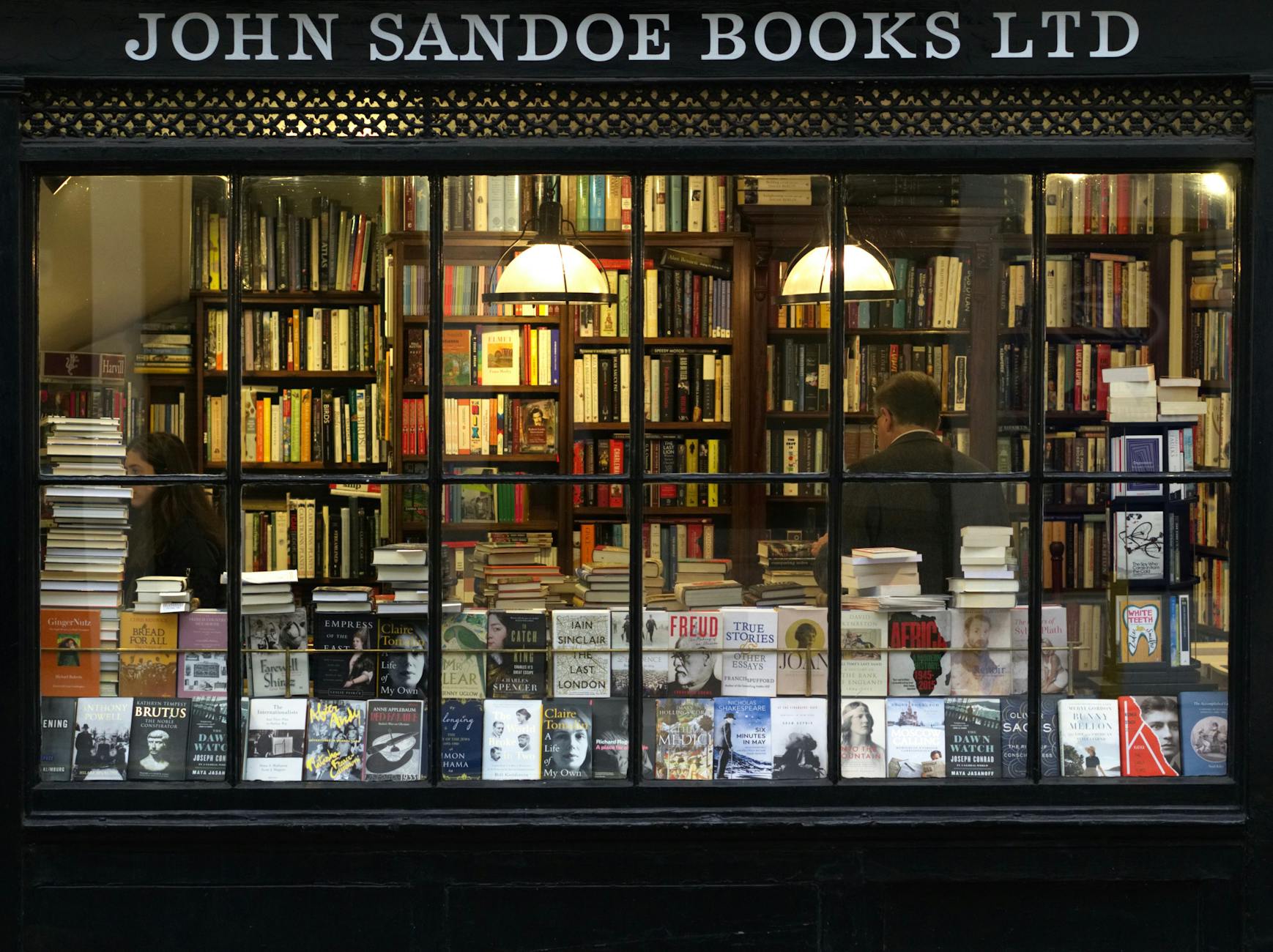

From this perspective, it’s not hard to see why I might have been frustrated by my encounters with the publishing industry and would end up looking for another path. This isn’t to demonize traditional publishing- to this day, most of what I read comes from either a big commercial or university press, with a smattering of books by smaller speciality publishers and hardly anything self-published. There are overpowering economic reasons for why large-scale publishing operates the way that it does, and the people within the industry do their best to produce good books within the limits of their situation. But the industry is beyond my power to change, so if I wanted to do things differently, I needed to seek out alternatives.

Enter self-publishing. I’ll admit that part of why it took me so long to look into self-publishing is because I was prejudiced against it. Before I realized how difficult, opaque, and slow-moving traditional publishing could be, I assumed that anyone with a good book would ultimately find their way to the shelves of a brick-and-mortar bookstore, and that self-publishing was for the quacks, cranks, and rejects. But when I looked into it, I found that readers had embraced self-published books to a much greater extent than I expected, and there was a much greater variety of books and writers.

Chastened by my own experience and my new understanding that marketability, not quality, was often the biggest hurdle to getting a book published traditionally, I realized that self-publishing created opportunities for writers with all kinds of passion projects and niche works, coming from all kinds of unusual backgrounds. Many of these were not books that I personally wanted to read, but they were there for someone. There certainly were some quacks, cranks, and rejects, but there are several high-earning, traditionally published authors who I would put in that same category. It was unfair of me to assume that the average self-published book was necessarily worse than the average book that made it through the agent-editor-publisher gauntlet.

There are a few crucial advantages to self-publishing- particularly through Amazon Kindle Publishing, my platform of choice- that sealed the deal for me. First, there is the publishing timeline. While traditional publishing can often take a full year to turn the author’s finished, approved manuscript into a physical book, platforms like AKP can handle this process in the space of a couple weeks. The quick turnaround from manuscript to book on sale means you can publish as quickly as you write. Unlike in traditional publishing, where publishing a book can be a years-long process and an initial failure could be fatal to your career, self-publishing allows you to quickly publish new works, whether to follow up on success or to adjust to setbacks.

It also costs nothing to finalize a book and list it for sale, and copies are only produced on-demand to match orders. AKP collects its cut from each copy sold, but you have no up-front costs, unlike in older forms of self-publishing (often called “vanity publishing”), in which you pay a small press up-front for them to run a certain number of copies of your book and the onus is then on you to make back the money already spent by hawking those copies to your friends and relatives. That means that even if you don’t expect to make much money off of sales, you at least don’t have to worry about incurring a loss (spending on ads is another matter, but I haven’t done this myself and have no insights to share on it).

Lastly, you have complete control over the genre classification and keywords of your book. You can use this simply to match your book to its specific intended audience, or you can use this tactically to increase the odds that it will appear in unexpected corners of the marketplace. An advantage of listing your book in certain niche genres is that it sometimes takes only a handful of sales for your book to jump towards the top of the genre list- shortly after publication, The Myth of the Thucydides Trap briefly appeared near the very top of one of its sub-genres, listed just behind works by the famous academic Noam Chomsky and the ambassador Kishore Mahbubani. This can greatly increase your odds of being discovered by readers searching for traditionally published books in your genre.

These advantages enabled me to publish two books in the space of half a year, with additional works coming as quickly as I am able to write and edit them. I can write whatever kinds of books I choose to, while keeping complete control over everything from the cover design to the sale price. This is a kind of autonomy and freedom that traditionally published authors never obtain. But… how’s the money? Next week, I’ll write on my experiences with the business side of self-publishing, and my honest view of today’s market for self-published books.

Leave a comment