The early modern era, from the 16th to the 19th century, was one of the most violent and unstable in European history. But over the same period, East Asia experienced centuries of peace between the major nations of China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The contrasts between Europe’s era of warfare and upheaval and East Asia’s era of peaceful stability- happening at the same time on opposite ends of Eurasia- explain many of the most important events of the past few centuries, and give hints of what may come in the future.

The fields of political science and international relations have an unfortunate habit of focusing too narrowly on Europe and ignoring or undervaluing the experiences of other parts of the world. But, as I pointed out in my post on the work of Xinru Ma and David Kang, this is beginning to change for the better. One way this has taken shape is a new interest in the dynamics of war and peace outside of Europe. Classic studies of European international relations have shown patterns of frequent conflict, unstable balances of power, and shifting alliances, but other parts of the world have shown very different trends. In East Asia, for instance, the early modern period was marked by long stretches of peace, a stable regional order, and very steady relations between each of the key powers- a “Confucian Long Peace,” based on shared Confucian ideology and values.

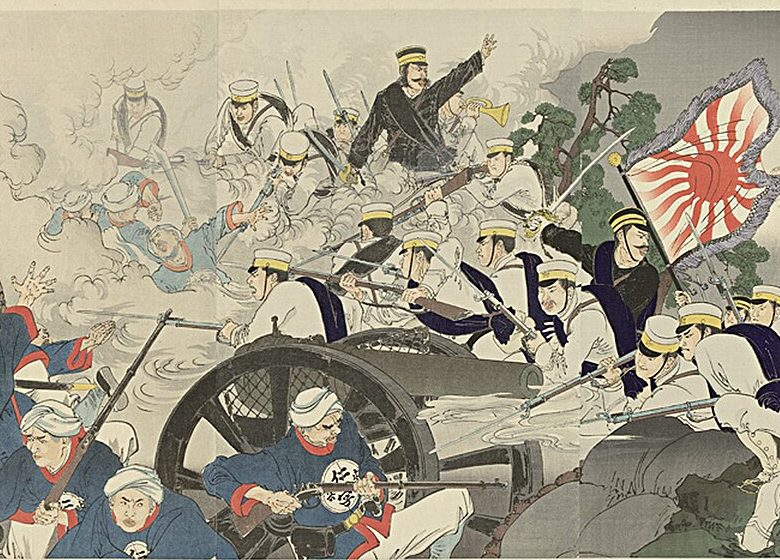

By the narrowest definition, the Long Confucian Peace lasted three centuries, spanning from the Imjin War of 1592-1598 to the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. A more generous definition could push the origins of a Confucian Peace between China, Korea, and Vietnam- not yet including Japan- back by a century or more, as the Ming Dynasty of China (1366-1644) solidified a peaceful relationship with the neighboring Joseon kingom of Korea and with the Le dynasty of Vietnam during the first few decades of its rule. This mainland long peace held for almost five hundred years, ending only with the French conquest of Vietnam in the 1880s and Japanese conquest of Korea in the 1890s. In both cases, Chinese forces fought to repel the invaders and maintain the independence of their Korean and Vietnamese ally-tributaries.

In the era of the Confucian Long Peace, the contrast between East Asia and Europe is stark. While East Asia settled into a peaceful and highly stable international order, Europe was wracked by devastating wars between ever-shifting alliances of rival powers. Dynastic struggles and the Protestant Reformation led to the European wars of religion in the 16th and 17th centuries, devastating the entire continent. Just one of these conflicts, the Thirty Years’ War fought between the Holy Roman Emperor and his enemies, is estimated to have killed nearly a third of the population of central Europe. While Confucian East Asia passed the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries in relative peace, Europeans would fight countless wars over colonies, royal inheritances, surging nationalism, and revolutionary ideals.

Political scientists broadly agree that this era of violence and upheaval in Europe was crucial for the development of the modern state, market capitalism, and the modern global diplomatic system. In my book The Myth of the Thucydides Trap, I take a close look at many of these major conflicts and how they’ve shaped the modern world. Constant fighting drove the development of advanced weapons and tactics, forging the leading European armies and navies into world-beating machines of conquest. The expense of supporting these deadly, professional forces spurred European governments to raise taxes more efficiently and to issue public debt so that wartime costs could be paid off later, during peacetime. Ever-shifting relations between many rival powers also called for a system of treaties and international laws, which would eventually mature into today’s system of worldwide diplomacy through international bodies like the United Nations.

Meanwhile in East Asia, the biggest, most populous, most technologically advanced countries enjoyed centuries of peace with one another. Though they continued to wage war against peoples outside of the Confucian system- steppe nomads, hill tribes, pirates, and so on- fighting was generally of a small scale and low intensity compared to massive European conflicts like the Italian Wars, the Wars of Religion, or the Napoleonic Wars. As such armies were often underpaid and undertrained, talented people rarely went into military service, and advances in weapons, organization, or tactics were few and far between. Even though the economies and populations of these countries boomed over the course of the Confucian Long Peace, rulers felt little need to tap into this growth to make their central governments stronger, better funded, or more efficient. As a result, they found it difficult to raise large armies in times of crisis and even harder to pay for them.

This set the stage for the collision between East and West in the 19th century. The Confucian countries of China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan were rich and populous, but militarily weak. On the eve of the First Opium War, the Qing Empire made up close to a quarter of the world’s population and economic output, yet its defense relied entirely on a decaying fleet of coastal patrol ships and a small, badly-equipped, undisciplined army scattered across its vast territory. Tiny Britain, in contrast, commanded professional armies and navies armed with the most advanced weapons and tactics, led by skilled officers, and ready for action on any continent on the globe. When war broke out between them in 1839-1841, a small British force borne on about 40 ships rampaged across China with almost total impunity, sinking fleets, sacking major cities across southern and central China, and blocking off the Grand Canal, threatening the Qing capital with starvation. The Qing court had no choice but to accept the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Nanjing, the first of many ‘unequal treaties’ that would be imposed on the Confucian countries at gunpoint.

This shocking defeat by the Western “barbarians” rattled the Confucian regimes to their cores. How could the vast empire of China been utterly defeated by such a small force of invaders? In each country, new divides emerged between reformers who wanted to embrace Western ideas and practices, conservatives who wanted to preserve Confucian institutions in their entirety, and moderates who attempted to split the difference. These simmering tensions erupted into purges, coups, and even civil wars.

At the same time, the First Opium War demonstrated to European colonizers that the Confucian states were soft targets. Western forces invaded China again in 1856, and launched probing attacks on Vietnam in 1858, in Japan in 1863, and in Korea in 1866 and 1871, driving home the threat of total colonization by the Western empires. The clash between Confucian ideology and the new geopolitical reality forced each country to make painful adjustments. Over the following decades, China chose to pursue a careful and tightly restricted modernization, Vietnam and Korea settled into conservative isolationism and dependence on Chinese protection, while Japan embraced a radical program of technological, political, and even cultural Westernization under the Meiji Emperor.

It was Japan’s decision to “Leave Asia“- that is, to defect from the old Confucian international system to the Western one- that sounded the death knell of the Confucian Long Peace. With that shift in perspective, Japanese elites no longer saw their counterparts in China, Korea, and Vietnam as peers and allies in a shared Confucian civilization. Rather, they came to see their former friends as benighted, ignorant, and in need of ‘education’ by a more enlightened nation like Japan. At the same time, the Japanese were aware that the only way to secure their place in the violent, competitive Western system was to expand their military and industrial strength and to seize colonies.

Japan’s new predatory attitude towards its East Asian neighbors became apparent during the Sino-French War of 1884-1885, an oft-forgotten conflict with a major historical impact. France invaded Vietnam with the goal of colonizing the entire country, while Vietnamese forces, reinforced by Qing government troops and Chinese mercenaries, resisted fiercely. Chinese forces had greatly improved their equipment and tactics since the Opium Wars, and eventually fought the French army to a standstill. At this point, Japan threatened to intervene- not on behalf of the Vietnamese and Chinese, Japan’s former friends and allies, but on behalf of the French colonizers. China folded, Vietnam lost its sovereignty, and Japan’s predatory attitude towards the old Confucian countries became apparent. A decade later, Japan invaded Korea and China in the First Sino-Japanese War, reducing Korea to a colony and seizing strategic ports and islands- including Taiwan- from China.

In short, the Confucian Long Peace held as long as the key states of East Asia held certain assumptions. First, there was the assumption of a fairly steady balance of power. China’s vast population and territory meant that it was, and would remain, the most dominant power in the region. Secondly, there was an assumption that the dominant power would act as a magnanimous friend and protector of weaker Confucian rulers. The entire system was based on the idea that the relationships between stronger and weaker powers should be symbioitic rather than predatory. As long as China was both powerful and friendly, the Long Peace could hold between the Confucian states. Challenges came when China’s dominance was questioned, as during the Imjin War, feudal Japan’s invasion of the Asian mainland. The system collapsed utterly when the belief in benevolent great powers was shattered, as occurred during the era of European colonization.

This has several important implications for the study of international relations and political science. Peaceful and equitable relations between countries, over the course of many centuries, are clearly possible. Yet the conditions that seem to enable this kind of Long Peace are delicate and easily disrupted. Not only the balance of power between states, but also the ideological perspectives and even individual personalities of leaders and diplomats, play important roles. We’ve seen this dynamic work at a regional level (East Asia) but collapse once outside forces become involved (Britain and France). If our goal for the modern world is a long, just peace between nations, more study is certainly needed- but the Confucian Long Peace is a great place to start.

Leave a comment